Osteoporosis

Highlights

Osteoporosis Risk Factors

- Age is the main risk factor for osteoporosis. Aging causes bones to thin and weaken. Although osteoporosis affects mostly postmenopausal women, older men are also at risk.

- Osteoporosis is more common in people who have a small, thin body frame and bone structure.

- Dietary calcium and vitamin D deficiencies are important factors in the risk for osteoporosis.

- Women who smoke, particularly after menopause, have a significantly greater risk of spine and hip fractures than those who do not smoke. Men who smoke also have lower bone density.

- Excessive alcohol consumption increases osteoporosis risk.

- Lack of exercise and a sedentary lifestyle can increase the risk of osteoporosis. Engaging in regular weight-bearing and resistance exercises (such as walking or strength training) can help prevent it.

Medications

- Bisphosphonates are the main drugs used for osteoporosis prevention and treatment. Alendronate (Fosamax, generic), risedronate (Actonel, generic), and ibandronate (Boniva, generic) come in pills that are taken by mouth. Zoledronic acid (Reclast) is given by once-yearly injection. Ibandronate is also available as a four-times a year injection. Denosumab (Prolia) is a new type of antiresorptive medication that works differently than bisphosphonates.

- Other types of drugs used for osteoporosis treatment and prevention include raloxifene (Evista), calcitonin, and teriparatide (Forteo).

FDA Reviewing Long-Term Use of Bisphosphonates

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is currently reviewing whether long-term (more than 3 - 5 years) use of bisphosphonate drugs provides any benefits for fracture prevention. Possible concerns for long-term use of bisphosphonates are increased risks for thigh bone (femoral fractures), esophageal cancer, and osteonecrosis (bone death) of the jaw.

Screening for Osteoporosis

- Updated guidelines from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) reinforce the recommendation that women receive bone mineral density (BMD) screening beginning at age 65. Postmenopausal women younger than age 65 should be screened only if they have significant risk factors for osteoporosis or bone fracture.

- A new study suggests that some women may be able to wait a much longer time between their screening tests than is current practice. Woman with a normal result may be able to wait for 15 years and those with mild osteopenia (bone thinning) for 5 years.

United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Recommendations

New recommendations from the USPSTF include:

- According to the USPSTF, there is insufficient evidence that daily low-dose amounts of vitamin D supplements, with or without calcium, can prevent fractures or other health problems such as cancer. Many other experts, however, recommend moderately high doses of vitamin D (800-1000 IU daily) along with a sufficient intake of dietary calcium.

- Hormone therapy replacement (HRT) should not be used for prevention of osteoporosis or other chronic health conditions.

Introduction

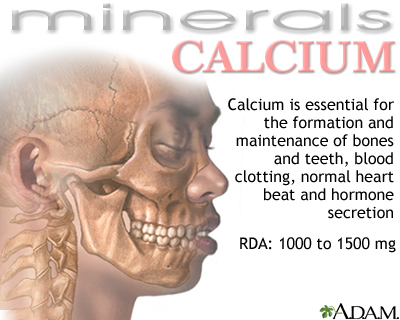

Osteoporosis is a progressive skeletal disease in which bones become thin, weak, brittle, and prone to fracture. Osteoporosis literally means “porous bones.” Thinning bones are caused by loss of bone density. Calcium and other minerals contribute to the bone mineral density that helps strengthen and protect bones.

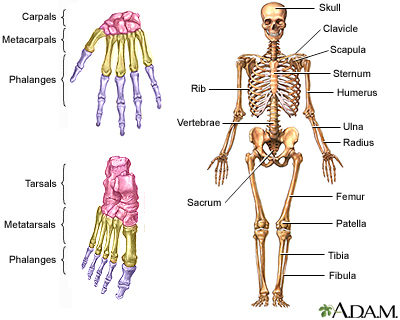

The Bones

Bones are made of living tissue that is constantly being broken down (resorbed) and formed again. The balance of bone build-up (formation) and break down (resorption) is controlled by a complex mix of hormones and chemical factors. If bone resorption occurs at a greater rate than bone formation, your bones lose density and you are at increased risk for osteoporosis.

Until a healthy adult is around age 40, the process of formation and resorption is a nearly perfectly coupled system, with one phase balancing the other. As a person ages, or in the presence of certain conditions, this system breaks down and the two processes become out of sync. Eventually, the breakdown of bone eventually overtakes the build-up.

In women, estrogen loss after menopause is particularly associated with rapid resorption and loss of bone density. Postmenopausal women are therefore at highest risk for osteoporosis and subsequent fractures.

Primary and Secondary Osteoporosis

Primary osteoporosis is the most common type of osteoporosis. It is usually age-related and associated with the postmenopausal decline in estrogen levels, or related to calcium and vitamin D insufficiency.

Secondary osteoporosis is osteoporosis caused by other conditions, such as hormonal imbalances, diseases, or medications.

Causes

The Role of Sex Hormones in Bone Breakdown

Women and Estrogen. A woman experiences a rapid decline in bone density after menopause, when her ovaries stop producing estrogen. Estrogen comes in several forms:

- The strongest form of estrogen is estradiol.

- The other important but less powerful estrogens are estrone and estriol.

The ovaries produce most of the estrogen in the body, but estrogen can also be formed in other tissues, such as the adrenal glands, body fat, skin, and muscle. After menopause, some amounts of estrogen continue to be manufactured in the adrenals and in peripheral body fat. Even though the adrenals and ovaries stop producing estrogens directly, they continue to be a source of the male hormone testosterone, which converts into estradiol.

Estrogen may have an impact on bone density in various ways, including slowing bone breakdown (resorption).

Men and Androgens and Estrogen. In men, the most important androgen (male hormone) is testosterone, which is produced in the testes. Other androgens are produced in the adrenal glands. Androgens are converted to estrogen in various parts of a man’s body, including bone.

Studies suggest that falling levels of testosterone and estrogen can contribute to bone loss in elderly men. Both hormones are important for bone strength in men.

Vitamin D and Parathyroid Hormone Imbalances

Low levels of vitamin D and high levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH) are associated with bone density loss in women after menopause:

- Vitamin D is a vitamin with hormone-like properties. It is essential for the absorption of calcium and for normal bone growth. Lower levels result in impaired calcium absorption, which in turn causes an increase in parathyroid hormone (PTH).

- Parathyroid hormone is produced by the parathyroid glands. These are four small glands located on the surface of the thyroid gland. They are the most important regulators of calcium levels in the blood. When calcium levels are low, the glands secrete more PTH, which then increases blood calcium levels. High persistent levels of PTH stimulate bone resorption (bone mineral loss).

Causes of Secondary Osteoporosis

Secondary osteoporosis results from medications or other medical conditions.

Medications. Medications that can cause osteoporosis include:

- Oral corticosteroids (also called steroids or glucocorticoids) can reduce bone mass. Inhaled steroids may also cause bone loss when taken at higher doses for long periods of time.

- Loop diuretics, such as furosemide (Lasix, generic), increase the kidneys’ excretion of calcium, which can lead to thinning bones. Thiazide diuretics, on the other hand, protect against bone loss, but this protective effect ends after use is discontinued .

- Hormonal contraceptives that use progestin without estrogen (such as Depo-Provera injection or other progestin-based contraceptives), can cause loss of bone density. For this reason, Depo-Provera injections should not be used for longer than 2 years.

- Anticonvulsant (anti-seizure) drugs increase the risk for bone loss (as does epilepsy itself).

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which are used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease (“heartburn”), can increase the risk for bone loss and fractures when they are used at high doses for more than a year. These drugs include omeprazole (Prilosec, generic), lansoprazole (Prevacid), and esomeprazole (Nexium).

- Other drugs that increase the risk for bone loss include the blood-thinning drug heparin, and hormonal drugs that suppress estrogen (such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists and aromatase inhibitors).

Medical Conditions. Osteoporosis can be secondary to other medical conditions, including alcoholism, diabetes, thyroid imbalances, chronic liver or kidney disease, Crohn's disease, celiac disease, scurvy, rheumatoid arthritis, leukemia, cirrhosis, gastrointestinal diseases, vitamin D deficiency, lymphoma, hyperparathyroidism, anorexia nervosa, premature menopause, and rare genetic disorders such as the Marfan and Ehlers-Danlos syndromes.

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for osteoporosis are:

- Female gender

- Age over 65

- Menopause

- Low body weight

- Tobacco and excessive alcohol use

- Family history of fractures associated with osteoporosis

Gender

Seventy percent of people with osteoporosis are women. Men start with higher bone density and lose calcium at a slower rate than women, which is why their risk is lower. Nevertheless, older men are also at risk for osteoporosis.

Age

As people age, their risks for osteoporosis increase. Aging causes bones to thin and weaken. Osteoporosis is most common among postmenopausal women, and screening for low bone density is recommended for all women over the age of 65.

Ethnicity

Although adults from all ethnic groups are susceptible to developing osteoporosis, Caucasian and Asian women and men face a comparatively greater risk.

Body Type

Osteoporosis is more common in people who have a small, thin body frame and bone structure. Low body weight (less than 127 pounds or a BMI less than 21) is a risk factor for osteoporosis.

Family History

People whose parents had a fracture due to osteoporosis are themselves at increased risk for osteoporosis.

Hormonal Deficiencies

Women. Estrogen deficiency is a primary risk factor for osteoporosis in women. Estrogen deficiency is associated with:

- Menopause

- Surgical removal of ovaries

- Anorexia nervosa, (an eating disorder), or extreme low body weight can affect the body's production of estrogen

Men. Low levels of testosterone increase osteoporosis risk. Certain types of medical conditions (hypogonadism) and treatments (prostate cancer androgen deprivation) can cause testosterone deficiency.

Lifestyle Factors

Dietary Factors. Diet plays an important role in both preventing and speeding up bone loss in men and women. Calcium and vitamin D deficiencies are risk factors for osteoporosis. Other dietary factors may also be harmful or protective for certain people.

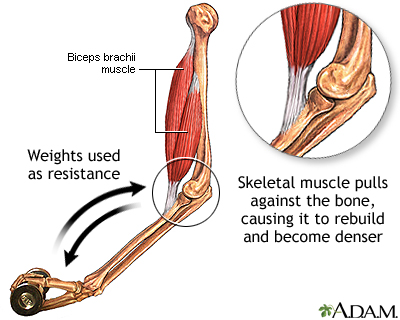

Exercise. Lack of exercise and a sedentary lifestyle increases the risk for osteoporosis. Conversely, in competitive female athletes, excessive exercise may reduce estrogen levels, causing bone loss. (The eating disorder anorexia nervosa can have a similar effect.) People who are chairbound or bedbound due to medical infirmities and who do not bear weight on the bones are at risk for osteoporosis.

Smoking. Smoking can affect calcium absorption and estrogen levels.

Alcohol. Excessive consumption of alcoholic beverages can increase the risk for bone loss.

Lack of Sunlight. Vitamin D is made in the skin using energy from the ultraviolet rays in sunlight. Vitamin D is necessary for the absorption of calcium in the stomach and gastrointestinal tract and is the essential companion to calcium in maintaining strong bones.

Risk Factors in Children and Adolescents

The maximum density that bones achieve during the growing years is a major factor in whether a person goes on to develop osteoporosis. People, usually women, who never develop adequate peak bone mass in early life are at high risk for osteoporosis later on. Children at risk for low peak bone mass include those who are:

- Born prematurely

- Have anorexia nervosa

- Have delayed puberty or abnormal absence of menstrual periods

Exercise and good nutrition during the first three decades of life (when peak bone mass is reached) are excellent safeguards against osteoporosis (and other health problems).

Complications

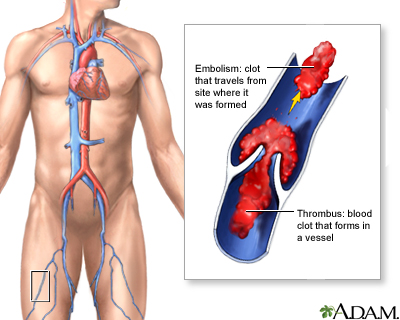

Low bone density increases the risk for fracture. Bone fractures are the most serious complication of osteoporosis. Spinal vertebral fractures are the most common type of osteoporosis-related fracture, followed by hip fractures, wrist fractures, and other types of broken bones. About 80% of these fractures occur after relatively minor falls or accidents. In addition to causing disability, hip fractures can increase the risk of early death. Complications of hip fractures include hospital-acquired infections and blood clots in the lungs.

Symptoms

Osteoporosis is usually quite advanced before symptoms appear. Unfortunately, a fracture of the wrist or hip is often the first sign of osteoporosis. These fractures can occur even after relatively minor trauma, such as bending over, lifting, jumping, or falling from a standing position.

Compression fractures can occur in the vertebrae of the spine as a result of weakened bone. Early spinal compression fractures may go undetected for a long time, but after a large percentage of calcium has been lost, the vertebrae in the spine start to collapse, gradually causing a stooped posture called kyphosis, or a "dowager’s hump." Although this is usually painless, patients may lose as much as 6 inches in height.

Diagnosis

Candidates for Bone Density Testing

Because osteoporosis can occur with few symptoms, testing is important. Bone density testing is recommended for:

- All women age 65 or older

- Women under age 65 with one or more risk factors for osteoporosis

- All men over age 70

- Men ages 50 - 70 with one or more risk factors for osteoporosis

In addition to age, the main risk factors for osteoporosis are:

- Low body weight (less than 127 pounds) or low body mass index (less than 21)

- Long-term tobacco use

- Excessive alcohol use

- Having a parent who had a fracture caused by osteoporosis

Other risk factors that may indicate a need for bone mineral density testing include:

- Long-term use of medications associated with low bone mass or bone loss such as corticosteroids, some anti-seizure medications, Depo-Provera, thyroid hormone, or aromatase inhibitors.

- History of treatment for prostate cancer or breast cancer

- History of medical conditions such as diabetes, thyroid imbalances, estrogen or testosterone deficiencies, early menopause, anorexia nervosa, rheumatoid arthritis

- Significant loss of height

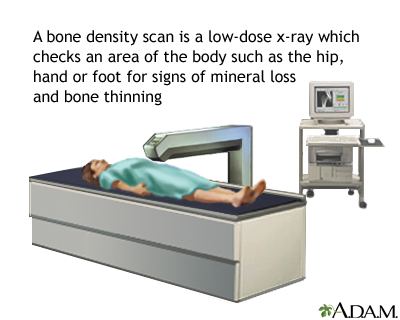

Tests Used for Measuring Bone Density

Central DXA. Bone densitometry is a test for measuring bone density. The standard technique for determining bone density is called dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). DXA is simple and painless and takes 2 - 4 minutes. The machine measures bone density by detecting the extent to which bones absorb photons that are generated by very low-level x-rays. (Photons are atomic particles with no charge.) Measurements of bone mineral density are generally given as the average concentrations of calcium in areas that are scanned.

Central DXA measures the bone mineral density at the hip, upper thigh bone (femoral neck), and spine.

Other Tests. Other tests may be used, but they are not usually as accurate as DXA. They include ultrasound techniques, DXA of the wrist, heels, fingers, or leg (peripheral DXA) and quantitative computed tomography (QCT) scan.

Screening tests using these technologies are sometimes given at health fairs or other non-medical settings. These screening tests typically measure peripheral bone density in the heels, fingers, or leg bones. The results of these tests may vary from DXA measurements of spine and hip. While these peripheral tests may help indicate who requires further BMD testing, a central DXA test is required to diagnose osteoporosis and to monitor treatment response.

Diagnosing Osteoporosis and Predicting the Risk for Fracture

Osteoporosis is diagnosed when bone density has decreased to the point where fractures can result from mild stress, the so-called fracture threshold. This is determined by measuring bone density and comparing the results with the norm, which is defined as the average bone mineral density in the hipbones of a healthy 30-year-old adult.

The doctor then uses this comparison to determine the standard deviation (SD) from this norm. Standard deviation results are given as Z and T scores:

- The T score gives the standard deviation of the patient in relationship to the norm in young adults. Doctors often use the T-score and other risk factors to determine the risk for fracture.

- The Z score gives the standard deviation of the patient in relationship to the norm in the patient’s own age group and body size. Z scores may be used for diagnosing osteoporosis in younger men and women. They are not normally used for postmenopausal women or for men age 50 and older.

Results of T-scores indicate:

- Higher than -1 indicates normal bone density.

- Between -1 and -2.5 indicates low bone density (osteopenia).

- A score of -2.5 or lower indicates a diagnosis of osteoporosis.

The lower the T-score, the lower the bone density, and the greater the risk for fracture. In general, doctors recommend beginning medication when T-scores are -2.5 or below. Patients who have other risk factors may need to begin medication when they have osteopenia (scores between -1 and -2.5). Osteopenia refers to bone mineral density that is lower than normal, but not low enough to be classified as osteoporosis. Osteopenia is considered a precursor to osteoporosis.

Doctors don’t yet know the best testing schedule for women whose first test does not reveal osteoporosis. A recent study suggests that such women may be able to wait a much longer time between screening tests than is current practice. Woman with a normal result may be able to wait for 15 years, those with mild osteopenia (bone thinning) for 5 years, and those with more advanced osteopenia for 1 year.

Laboratory Tests

In certain cases, your doctor may recommend that you have a blood test to measure your vitamin D levels. A standard test measures 25-hydroxyvitamin D, also called 25(OH)D. Depending on the results, your doctor may recommend you take vitamin D supplements.

Lifestyle Changes

Healthy lifestyle habits, including adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, are important for preventing osteoporosis and supporting medical treatment.

Calcium and Vitamin D

A combination of calcium and vitamin D can reduce the risk of osteoporosis. (For strong bones, people need enough of both calcium and vitamin D.) The best sources are from calcium-rich and vitamin D-fortified foods.

The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommends:

- Adults under age 50 should have 1,000 mg of calcium and 400 - 800 IU of vitamin D daily.

- Adults age 50 and older should have 1,200 mg of calcium and 800 - 1,000 IU of vitamin D daily.

Dietary Sources. Good dietary sources of calcium include:

- Milk, yogurt, and other dairy products

- Dark green vegetables such as collard greens, kale, and broccoli

- Sardines and salmon with bones

- Calcium-fortified foods and beverages such as cereals, orange juice, soymilk

Certain types of foods can interfere with calcium absorption. These include foods high in oxalate (such as spinach and beet greens) or phytate (peas, pinto beans, navy beans, wheat bran). Diets high in animal protein, sodium, or caffeine may also interfere with calcium absorption.

Dietary sources of vitamin D include:

- Fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, and tuna

- Egg yolks

- Liver

- Vitamin D-fortified milk, orange juice, soymilk, or cereals

However, many Americans do not get enough vitamin D solely from diet or exposure to sunlight.

Supplements. Doctors are currently reconsidering the use of calcium and vitamin D supplements. A 2012 recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) advised that healthy postmenopausal women may not require these supplements. According to the USPSTF, there is not enough evidence to prove that taking daily low-dose amounts of vitamin D supplements, with or without calcium, can prevent fractures or other health problems such as cancer. Other experts, however, recommend moderately high doses of vitamin D (800-100 IU daily) along with a sufficient intake of dietary calcium.

In addition to possible lack of benefit, calcium and vitamin D supplements are associated with certain risks, like kidney stones. Some studies suggest that calcium supplements may also increase the risk for heart attack. However, supplements may be appropriate for certain people including those who do not get enough vitamin D through sunlight exposure and those who do not consume enough calcium in their diet. Talk with your doctor about whether or not you should take supplements.

Calcium and vitamin D supplements can be taken as separate supplements or as a combination supplement. If separate preparations are used, they do not need to be taken at the same time.

- Calcium supplements include calcium carbonate (Caltrate, Os-Cal, Tums), calcium citrate (Citracal), calcium gluconate, and calcium lactate. Although each kind provides calcium, they all have different calcium concentrations, absorption capabilities, and other actions.

- Vitamin D is available either as D2 (ergocalciferol) or D3 (cholecalciferol). They work equally well for bone health.

Exercise

Exercise is very important for slowing the progression of osteoporosis. Although mild exercise does not protect bones, moderate exercise (more than 3 days a week for more than a total of 90 minutes a week) reduces the risk for osteoporosis and fracture in both older men and women. Exercise should be regular and life-long. Before beginning any strenuous exercise program, talk to your doctor.

Specific exercises may be better than others:

- Weight-bearing exercise applies tension to muscle and bone and can help increase bone density in younger people. Weight training is also beneficial for middle-aged and older people.

- Regular brisk long walks improve bone density and mobility. Most older individuals should avoid high-impact aerobic exercises (step aerobics), which increase the risk for osteoporotic fractures. Although low-impact aerobic exercises such as swimming and bicycling do not increase bone density, they are excellent for cardiovascular fitness and should be part of a regular regimen.

- Exercises specifically targeted to strengthen the back may help prevent fractures later on in life and can be beneficial in improving posture and reducing kyphosis (hunchback).

- Low-impact exercises that improve concentration, balance, and strength, particularly yoga and tai chi, may help to decrease the risk of falling.

Other Lifestyle Factors

Other lifestyle changes that can help prevent osteoporosis include:

- Limit alcohol consumption. Excessive drinking is associated with brittle bones.

- Limit caffeine consumption. Caffeine may interfere with the body’s ability to absorb calcium.

- Quit smoking. The risk for osteoporosis from cigarette smoking appears to diminish after quitting.

Preventing Falls and Fractures

An important component in reducing the risk for fractures is preventing falls. Risk factors for falling include:

- Slow walking

- Inability to walk in a straight line

- Certain medications (such as tranquilizers and sleeping pills)

- Low blood pressure when rising in the morning

- Poor vision

Recommendations for preventing falls or fractures from falls include:

- Exercise to maintain strength and balance if there are no conflicting medical conditions.

- Do not use loose rugs on the floors.

- Move any obstructions to walking, such as loose cords or very low pieces of furniture, away from traveled areas.

- Rooms should be well lit.

- Have regular eye checkups.

- Consider installing grab bars in bathrooms especially near shower, tub, and toilet.

Medications

Two types of drugs are used to prevent and treat osteoporosis:

- Antiresorptive Drugs. Antiresorptives include bisphosphonates, selective estrogen-receptor modulators (SERMs), and calcitonin. Bisphosphonates are the standard drugs used for osteoporosis. Denosumab (Prolia) is a newer type of antiresorptive. These drugs block resorption (preventing bone break down), which slows the rate of bone remodeling, but they cannot rebuild bone. Because resorption and reformation occur naturally as a continuous process, blocking resorption may eventually also reduce bone formation.

- Anabolic (Bone-Forming) Drugs. Drugs that rebuild bone are known as anabolics. The primary anabolic drug is low-dose parathyroid hormone (PTH), which is administered through injections. This drug may help restore bone and prevent fractures. PTH is still relatively new, and long-term effects are still unknown. Fluoride is another bone-building drug, but it has limitations and is not commonly used.

Both types of drugs are effective in preventing bone loss and fractures, although they may cause different types of side effects. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends that these drugs should be prescribed only to patients who have been diagnosed with osteoporosis.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates are the primary drugs for preventing and treating osteoporosis. They can help reduce the risk of both spinal and hip fractures, including among patients with prior bone breaks.

Studies indicate that these drugs are effective and safe for up to 5 years. Eventually, however, bone loss continues with bisphosphonates. This may be due to the fact that bone breakdown is one of two phases in a continuous process of rebuilding bone. Over time, blocking resorption interrupts this process and impairs the second half of the process -- bone formation.

Candidates. Clinical guidelines recommend that the following people should take or consider taking bisphosphonates:

- Any woman who has a T score of -2.5 or lower on a DXA scan

- Women who have a T score between -1 and -2.5 (indicates low bone density [osteopenia]) and a history of fractures

Brands. Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis prevention and treatment are available in different forms:

- Oral bisphosphonates. These pills include alendronate (Fosamax, generic), risedronate (Actonel, generic), and ibandronate (Boniva, generic). Alendronate and risedronate are taken once a week. Ibandronate is available as a once-monthly pill. Risedronate is also available as a once-a-month pill and in a pill that contains calcium. Alendronate is available in a formulation that has vitamin D. Risedronate and alendronate are approved for both men and women.

- Injectable bisphosphonates. Zoledronic acid (Reclast) is approved for treatment and prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. It is given as a once-yearly injection. The injectable form of ibandronate (Boniva) requires injections 4 times a year. Injectable bisphosphonates are an alternative for patients who may have difficulty swallowing pills or sitting upright after oral bisphosphonate treatment.

Side Effects. The most distressing side effects of bisphosphonates are gastrointestinal problems, particularly stomach cramps and heartburn. These symptoms are very common and occur in nearly half of all patients. Other side effects may include irritation of the esophagus (the tube that connects the mouth to the stomach) and ulcers in the esophagus or stomach. Some patients may have muscle and joint pain. To avoid stomach problems, doctors recommend:

- Take the pill on an empty stomach in the morning with 6 - 8 ounces of water (not juice or carbonated or mineral water).

- After taking the pill, remain in an upright position. Do not eat or drink for at least 30 - 60 minutes. (Check your drug’s dosing instructions for exact time.)

- If you develop chest pain, heartburn, or difficulty swallowing, stop taking the drug and see your doctor.

Other Concerns. The FDA is currently reviewing whether long-term (more than 3 - 5 years) use of bisphosphonate drugs provides any benefits for fracture prevention. Possible concerns for long-term use of bisphosphonates are increased risks for thigh bone (femoral fractures), esophageal cancer, and osteonecrosis (bone death) of the jaw. The FDA recommends that doctors periodically reevaluate patients who have been on bisphosphonates for more than 5 years. Patients should inform their doctors if they experience any new thigh or groin pain, swallowing difficulties, or jaw or gum discomfort. Do not stop taking your medication unless your doctor tells you to do so.

For the injectable drug zoledronic acid (Reclast), kidney failure is a rare but serious side effect. Zoledronic acid should not be used by patients with risk factors for kidney failure.

Denosumab (Prolia)

Denosumab (Prolia) is a newer drug approved for treatment of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women who are at high risk for fracture. Denosumab is the first “biological therapy” drug approved for osteoporosis. It is considered an antiresorptive drug, but it works in a different way than bisphosphonates. It is a monoclonal antibody that works by targeting RANKL, a chemical factor involved with bone resorption.

Denosumab slows down the bone-breakdown process. However, because it also slows down the bone build-up and remodeling process, it is unclear what its longterm effects may be. Possible concerns are that denosumab may slow the healing time for broken bones or cause unusual fractures. For now, denosumab is recommended for women who cannot tolerate or who have not been helped by other osteoporosis treatments.

Denosumab is given as an injection in a doctor’s office twice a year (once every six months). Common side effects include back pain, pain in the arms and legs, high cholesterol levels, muscle pain, and bladder infection. Denosumab can lower calcium levels and should not be taken by women who have low blood calcium levels (hypocalcemia) until this condition is corrected.

Because denosumab is a biologic drug, it can affect or weaken the immune system and may increase the risk for serious infections. Other potential adverse effects include inflammation of the skin (dermatitis, rash, eczema) and inflammation of the inner lining of the heart (endocarditis). Denosumab may increase the risk of jaw bone problems such as osteonecrosis.

SERMs

Raloxifene (Evista) belongs to a class of drugs called selective estrogen-receptor modulators (SERMs). These drugs are similar, but not identical, to estrogen. Raloxifene provides the bone benefits of estrogen without increasing the risks for estrogen-related breast and uterine cancers.

While there are many SERM drugs, raloxifene is the only one approved for both treatment and prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Studies indicate that raloxifene can stop the thinning of bone and help build better quality and stronger bone. Raloxifene is recommended for postmenopausal women with low bone mass or younger postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. It can help prevent bone loss and reduce the risk of vertebral (spine) fractures. It is less clear how effective it is for preventing other types of fractures. Raloxifene is taken as a pill once a day.

Side Effects. Raloxifene increases the risk for blood clots in the veins. Because of this side effect, raloxifene also increases the risk for stroke (but not other types of cardiovascular disease). These side effects, though rare, are very serious. Women should not take this drug if they have a history of blood clots, or if they have certain risk factors for stroke and heart disease. More common mild side effects include hot flashes and leg cramps.

Parathyroid Hormone

Teriparatide (Forteo), an injectable drug made from selected amino acids found in parathyroid hormone, may help reduce the risks for spinal and non-spinal fractures. Although high persistent levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH) can cause osteoporosis, daily injections of low doses of this hormone actually stimulate bone production and increase bone mineral density. Teriparatide is usually recommended for patients with osteoporosis who are at high risk of fracture.

Side effects of PTH are generally mild and include nausea, dizziness, and leg cramps. No significant complications have been reported to date.

Early animal studies reported bone tumors in mice that were given parathyroid long-term. Such effects have not been observed in humans to date. However, people with Paget disease, (a disorder in which bone thickens but also weakens), should not take parathyroid hormone, because they are at higher than normal risk for bone tumors.

Calcitonin

Produced by the thyroid gland, natural calcitonin regulates calcium levels by inhibiting the osteoclastic activity, the breakdown of bone. The drug version is derived from salmon and is available as a nasal spray (Miacalcin, generic) and an injected form (Calcimar, Miacalcin, generic). Calcitonin is not used to prevent osteoporosis. It treats osteoporosis. It may be effective for spinal protection (but not hip) in both men and women. Calcitonin may be an alternative for patients who cannot take a bisphosphonate or SERM. It also appears to help relieve bone pain associated with established osteoporosis and fracture.

Side Effects. Side effects include headache, dizziness, anorexia, diarrhea, skin rashes, and edema (swelling). The most common adverse effect experienced with the injection is nausea, with or without vomiting. This occurs less often with the nasal spray. The nasal spray may cause nosebleeds, sinusitis, and inflammation of the membranes in the nose. Also, many people who take calcitonin develop resistance or allergic reactions after long-term use.

Hormone Replacement Therapy

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was formerly used to prevent osteoporosis, but is rarely used for this purpose today. Studies have shown that estrogen increases the risk for breast cancer, blood clots, strokes, and heart attacks. For this reason, women need to balance the benefits that HRT has on bone-loss protection, with the risks it carries for other serious health conditions. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends against the use of HRT for prevention of osteoporosis. [For more information on HRT, see In-Depth Report #40: Menopause.]

Resources

- www.nof.org -- National Osteoporosis Foundation

- www.niams.nih.gov/Health_Info/Bone -- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- www.iofbonehealth.org -- International Osteoporosis Foundation

- www.menopause.org -- North American Menopause Society

References

Black DM, Kelly MP, Genant HK, Palermo L, Eastell R, Bucci-Rechtweg C, et al. Bisphosphonates and fractures of the subtrochanteric or diaphyseal femur. N Engl J Med. 2010 May 13;362(19):1761-71. Epub 2010 Mar 24.

Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011 Apr 19;342:d2040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2040.

Chung M, Lee J, Terasawa T, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Vitamin D with or without calcium supplementation for prevention of cancer and fractures: an updated meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Dec 20;155(12):827-38.

Committee on Practice Bulletins-Gynecology, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin N. 129. Osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Sep;120(3):718-34. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31826dc446.

Cummings SR, San Martin J, McClung MR, Siris ES, Eastell R, Reid IR, et al. Denosumab for prevention of fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 20;361(8):756-65. Epub 2009 Aug 11.

Gourlay ML, Fine JP, Preisser JS, May RC, Li C, Lui LY, et al. Bone-density testing interval and transition to osteoporosis in older women. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jan 19;366(3):225-33.

Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, Heaney RP, et al. Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011 Jul;96(7):1911-30. Epub 2011 Jun 6.

Kennel KA, Drake MT. Adverse effects of bisphosphonates: implications for osteoporosis management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009 Jul;84(7):632-7.

Khosla S. Increasing options for the treatment of osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 20;361(8):818-20. Epub 2009 Aug 11.

Lewiecki EM. In the clinic. Osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Jul 5;155(1):ITC1-1-15; quiz ITC1-16.

Li K, Kaaks R, Linseisen J, Rohrmann S. Associations of dietary calcium intake and calcium supplementation with myocardial infarction and stroke risk and overall cardiovascular mortality in the Heidelberg cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study (EPIC-Heidelberg). Heart. 2012 Jun;98(12):920-5.

Lim LS, Hoeksema LJ, Sherin K; ACPM Prevention Practice Committee. Screening for osteoporosis in the adult U.S. population: ACPM position statement on preventive practice. Am J Prev Med. 2009 Apr;36(4):366-75.

National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2010.

Nelson HD, Walker M, Zakher B, Mitchell J. Menopausal hormone therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions: a systematic review to update the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendations. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jul 17;157(2):104-13.

North American Menopause Society. Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: 2010 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2010 Jan-Feb;17(1):25-54; quiz 55-6.

Park-Wyllie LY, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN, Hawker GA, Gunraj N, Austin PC, et al. Bisphosphonate use and the risk of subtrochanteric or femoral shaft fractures in older women. JAMA. 2011 Feb 23;305(8):783-9.

Qaseem A, Snow V, Shekelle P, Hopkins R Jr., Forciea MA and Owens DK. Pharmacologic treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(6): 404-15.

Silverman SL, Landesberg R. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and the role of bisphosphonates: a critical review. Am J Med. 2009 Feb;122(2 Suppl):S33-45.

Tang BM, Eslick GD, Nowson C, Smith C, Bensoussan A. Use of calcium or calcium in combination with vitamin D supplementation to prevent fractures and bone loss in people aged 50 years and older: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2007 Aug 25;370(9588):657-66.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for osteoporosis: U.S. preventive services task force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Mar 1;154(5):356-64. Epub 2011 Jan 17.

Warensjö E, Byberg L, Melhus H, Gedeborg R, Mallmin H, Wolk A, et al. Dietary calcium intake and risk of fracture and osteoporosis: prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ. 2011 May 24;342:d1473. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1473.

Watts NB, Diab DL. Long-term use of bisphosphonates in osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Apr;95(4):1555-65. Epub 2010 Feb 19.

Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, Drake MT, Eastell R, Orwoll ES, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Jun;97(6):1802-22.

Whitaker M, Guo J, Kehoe T, Benson G. Bisphosphonates for osteoporosis--where do we go from here? N Engl J Med. 2012 May 31;366(22):2048-51. Epub 2012 May 9.

|

Review Date:

12/19/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |